CIS700-Real-World-Robot-Learning

Robot Perception 2: Intelligence w/o Representations, Designing Action-Based Sensors

Tony Wang

02/06/2025

Intelligence in Robots: Get Rid of Representations & Designing Task-Focused Sensing

Introduction

Robots have come a long way since the earliest ideas of AI. Initially, people believed that in order for robots to be truly “intelligent,” they had to maintain elaborate symbolic or model-based representations of the world. The robot, so the thinking went, needed to build an internal “map” of everything around it before it could make decisions.

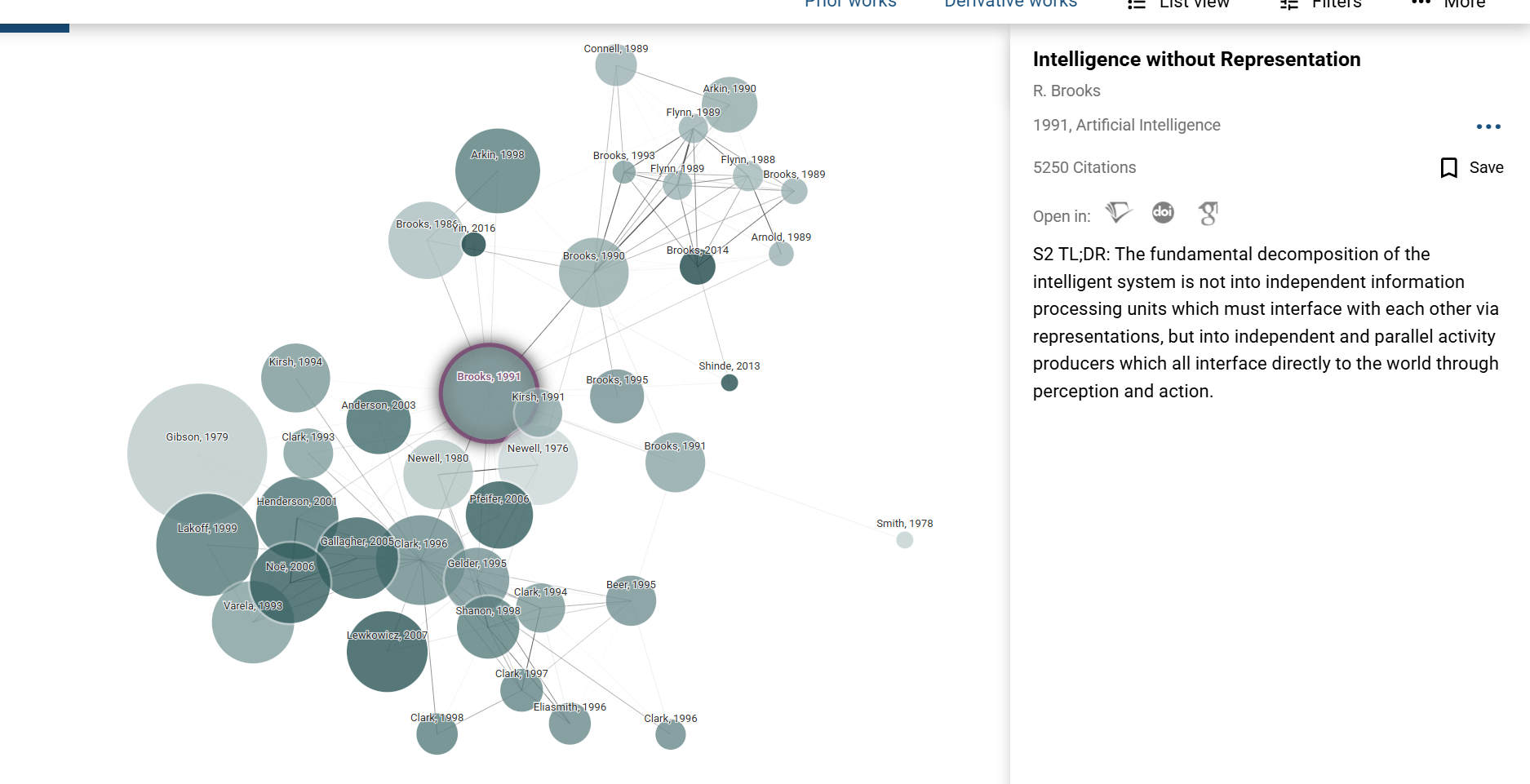

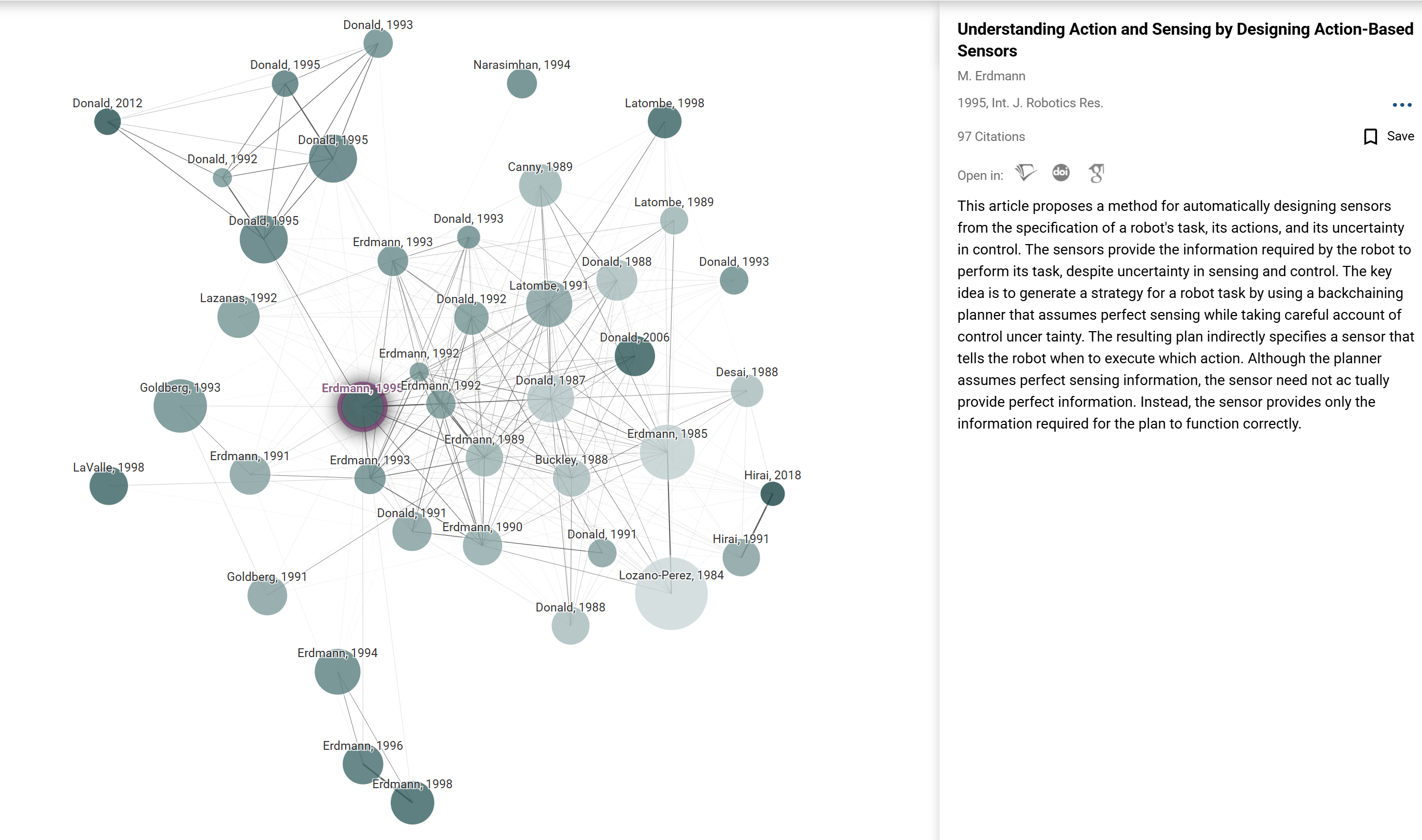

Here let we go through two classic research—Rodney Brooks’s “Intelligence without Representation” (1991) and Michael Erdmann’s “Understanding Action and Sensing by Designing Action-Based Sensors” (1995). Looking back, they offered radical new ways to think about intelligence and perception. Their insights continue to echo in present-day robotics, from agile warehouse robots to autonomous vehicles, and even in SOTA embodied AI paper like ReKep, OpenVLA and Pi0.

Aristotle’s “de anima” proprioception is the sense of the position of one’s own limbs and body in space. very similar to joint-based control in robotics

1. A Shift Away from Heavy Representations

In Intelligence without Representation, Brooks describes experiments where small mobile robots roam real-world environments—hallways, offices, labs—without maintaining an internal, complex model of their surroundings. Instead, these robots rely on many layers of simple behaviors (or “activities”) that connect sensing directly to action. This is now known as the subsumption architecture.

Rather than reasoning over an abstract “world model,” the robots simply had:

- A layer to avoid walls or obstacles.

- A layer to wander around freely.

- Another layer to search for specific goals or landmarks.

These layers ran in parallel and could inhibit or suppress one another as needed. Crucially, each layer used real-time sensor feedback instead of a centralized map. Observers found that these simple, tightly coupled “sense-act” loops produced surprisingly robust behavior. Brooks’s results led him to argue that complex internal representations are often unnecessary, at least for insect-level or reactive tasks.

Modern Echoes

This approach predicted a lot of the “embodied” or “behavior-based” robotics we see now: low-latency sensorimotor policies, reactive control, and minimal reliance on complete world models. Many delivery drones, swarm robots, and quadruped robots use specialized controllers that skip building fully detailed maps, opting instead for direct coupling of sensors to motors—augmented by targeted learning modules if needed.

2. Task-Centered Sensors

Meanwhile, Michael Erdmann’s “Understanding Action and Sensing…” looks at the problem of why and how to sense. Instead of collecting all possible information, Erdmann proposes to design sensors that are intrinsically linked to the actions the robot can perform.

Erdmann shows that to accomplish a well-defined task—like inserting a peg into a hole, grasping an object, or balancing a part on a post—the robot only needs enough sensing to pick an action guaranteed to make progress. Any additional sensors (e.g., full 3D maps, high-res cameras from multiple viewpoints) might be overkill.

He introduces mathematical constructs called progress cones: they define the set of states in which a certain action will reduce the “distance” to the goal. A robot that can identify which progress cone it’s in—even coarsely—then knows which action to take next. It doesn’t need to know its exact coordinates or a global map; it just needs to know which action is “safe” or “correct” from its current situation.

Modern Echoes

This notion is relevant in:

- Minimalistic grippers that detect contact normals rather than the entire 3D shape of a part.

- Low-resolution range sensors on mobile robots that only need to detect if turning left or right gets them closer to the goal without collisions.

- Active sensing strategies in which a robot deliberately moves in ways that reveal exactly the information it requires to keep making progress, rather than building a huge model “just in case.”

We see a growing trend of using specialized sensor suites—tiny 1D LiDAR for last-mile delivery, or a single camera coupled with learning-based policies—demonstrating that “less is more” if the sensor data is well-paired to the robot’s actions.

Archeologist

One key ancestor appears to be Rodney Brooks’s 1982 treatise, “Symbolic Error Analysis and Robot Planning,” which laid out concepts for analyzing how uncertainty propagates through a robot’s symbolic models—an influence clearly visible in Erdmann’s emphasis on factoring uncertainty into action-based sensor design. Moving forward in time, we see traces of Erdmann’s 1995 work shaping later scholarship like Steven LaValle’s “Planning Algorithms” (2006), which draws on similar ideas of leveraging geometry and uncertainty models to synthesize practical robot motion and sensing strategies.

Interestingly, though they do not directly cite Erdmann’s work, current SOTA embodied AI papers like 3D-viTAC, UMI and Pi0 are all following the same idea.

Overall, new robotic sensor research—like UMI and 3D-viTAC—carries on the same lineage as the late-20th-century “action-based sensing” philosophy: both approaches stress customizing perception to fit specific operational needs, thereby avoiding unnecessary global modeling. This strategy is particularly effective in scenarios that involve friction, deformation, and contact—domains that are highly localized yet strongly coupled to the robot’s actions. As hardware and algorithms continue to advance on both fronts, such “tightly coupled” sensor designs are likely to further broaden the scope of robotic systems.

3. Embodiment & Current Research Directions

Today’s robotics labs blend these principles with modern machine learning:

- Embodied AI. There is a push for AI agents—be they physical robots or simulated avatars—to learn policies by interacting in real or simulated worlds. Instead of building monolithic world models, many solutions exploit direct sensor-action coupling and rely on real-time feedback.

- Task-Driven Perception. Researchers increasingly ask, “What minimal set of features must be perceived for the robot to do its job reliably?” This resonates deeply with Erdmann’s approach, which shows how to systematically cut down the sensing problem to “what is needed for guaranteed progress.”

- Behavior-Based & Reactive Layers. Modern robot systems often combine reactive layers (à la Brooks’s subsumption) with higher-level strategic or planning layers. The layering ensures real-time reactivity when needed and more deliberate planning (possibly with partial or approximate models) when goals are more complex.

- Reduced Representations via Learning. Deep reinforcement learning and self-supervised methods sometimes produce “internal representations,” but these remain domain- and task-specific. The result still supports the original point: the best representation is the minimal one that solves the job at hand.

4. Practical Impact

- More robust robots. By stripping away heavy reliance on a full representation, robots become less fragile. If the environment deviates from a planned map, a robust robot can still react or gather information.

- Cost-effective solutions. Minimal sensors—like a single camera or a few simple IR sensors—are cheaper than multi-camera or LiDAR-based systems. For tasks like warehouse order-picking or agricultural harvesting, cost and reliability matter a lot.

- Adaptation to uncertainty. Both Brooks’s and Erdmann’s approaches face up to the fact that real-world sensors are noisy and the environment changes. By centering each control layer or sensor design on the real dynamics and the real environment, these frameworks are better poised to handle uncertainty gracefully.

Conclusion

The big paradigm shift, evident even in the earliest works of Brooks and Erdmann, was to move away from an obsession with large, explicit internal models of the environment toward a focus on tight, iterative loops of perception and action. Modern robotics is replete with these ideas: specialized, task-focused sensors; layered and reactive control; and learned or emergent internal states that remain tethered to physical tasks rather than universal knowledge representation.

As robotics researchers continue exploring new frontiers—home assistants, robotic surgery, space exploration—this underlying philosophy remains: A robot does not need to see and represent *everything*; it needs to know enough to act and succeed at its mission, no more. The environment itself, combined with carefully chosen sensors and intelligent, iterative control, can often serve as the robot’s best “model.”

Readings & Resources

- Brooks, R. A. (1991). Intelligence without Representation. Artificial Intelligence, 47(1-3), 139–159.

- Erdmann, M. A. (1995). Understanding Action and Sensing by Designing Action-Based Sensors. International Journal of Robotics Research, 14(5), 483–509.

- “Behavior-Based Robotics” by Ronald Arkin, discussing subsumption-style architectures.

- Latest research on “Embodied AI” in conference proceedings from ICRA, RSS, and CoRL.

Written by: Jie Wang GRASP Lab, UPenn

Feel free to share this post or email me with your thoughts and experiences on minimal sensors and action-based control in robotics!